Chapter 3: Review of the Process for Setting Intelligence Priorities

National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians Annual Report 2018

Introduction

80. As one of its first reviews, the Committee examined how the Government of Canada sets intelligence priorities. This review - the first since the Office of the Auditor General examined it in 1996 - provided the Committee with a broad view of the framework for how Cabinet and the various government departments and agencies involved in intelligence set and respond to priorities, requirements, and demands. This review is foundational. The Committee is new and has a mandate to review the framework of national security and intelligence in Canada. Future reviews will build on this one, as the Committee examines other parts of the framework to help support and maintain an effective, responsive, responsible, and accountable national security and intelligence community.

81. The Committee believes that it is uniquely placed to examine this issue. NSICOP is the first external and independent review body able to comprehensively examine national security and intelligence from a strategic perspective and across organizations, and with access to classified information. This allows it to review the process by which the security and intelligence community receives and responds to direction.

82. The importance of the process for setting intelligence priorities cannot be overstated. In Canada, Parliament serves as the highest form of democratic accountability. Ministers are accountable to Parliament and to Canadians for the activities and conduct of the departments and agencies in their portfolios. Within Cabinet, ministers are accountable to the Prime Minister. For most areas of public policy, this system encourages discussion and debate and is the foundation of ministerial accountability.

83. In the area of intelligence, ensuring accountability is a challenge. Intelligence is almost always classified to protect sources, methods, and access to targets, meaning that ministers and officials from organizations that collect or use intelligence cannot be publicly held to account the way that other officials can. Nor can they be as transparent about their activities and decisions. Intelligence activities have the potential to impact the rights of Canadians through, for example, intrusive investigative methods. Intelligence activities are also increasingly integrated, meaning that more than one minister is responsible for the overlapping activities of the security and intelligence community, which makes coordination particularly important.

84. Because of the sensitivity of targets, sources, and methods, the potential impact of intelligence activities on the rights of Canadians, and the possibility of gaps, intelligence activities carry an inherent amount of risk. For example, the disclosure of an intelligence target, such as a foreign state, could cause significant damage to Canada's foreign relations; the disclosure of a source identity could put an individual at significant risk. Another component of risk is "opportunity cost" - not all issues can be covered by a security and intelligence community of limited size and scope. Decisions must be made about where to focus and where not to focus, including by Cabinet at the strategic level.

85. Over time, the government has put in place measures to ensure the accountability of the security and intelligence community. These include legislation that defines the authorities and limitations of security and intelligence organizations, court warrants, and specialized review bodies. From a process perspective, the most important measure is the setting of intelligence priorities. It is the primary mechanism through which the government provides direction to the security and intelligence community and holds it accountable. In short, the intelligence priorities process is a vital part of ensuring accountability and managing risk.

86. The Committee examined the process for setting intelligence priorities from three angles. These were the governance of the process, the participation of the organizations involved, and performance measurement and resource expenditures. The Committee received significant information from ail departments and agencies involved in the process. Footnote 1 It conducted hearings with the Security and Intelligence Secretariat of the Privy Council Office (PCO), Public Safety Canada, CSIS, CSE, Global Affairs Canada, PCO's Intelligence Assessment Secretariat, the Integrated Terrorism Assessment Centre, and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. These organizations are representative of the key intelligence collectors and those with important coordination roles, intelligence clients with extensive requirements and those with program-specific requirements, and intelligence assessment organizations. The departments and agencies involved cooperated well with the Committee throughout the review process.

87. Overall, the Committee believes that the process for setting intelligence priorities has a solid foundation and has improved over time. Cabinet provides regular direction to the security and intelligence community. That direction is filtered through interdepartmental mechanisms into specific requirements that help guide the work of intelligence collectors and assessors. The process is governed by a defined committee structure and a performance measurement framework, which supports regular updates to ministers and Cabinet. However, every process can be improved and the security and intelligence community recognizes this. The Committee's review revealed challenges in a number of areas, some of which have already been identified by organizations within the security and intelligence community. These areas include inconsistencies in ministerial direction and the operational implementation of priorities, ensuring that Cabinet has sufficient information to support its discussions and decision-making, underdeveloped performance and financial reporting, and insufficient central leadership. The Committee believes that, together, these challenges can undermine ministerial accountability for intelligence activities.

88. These challenges should be addressed. As described earlier, accountability is a fundamental condition for the proper conduct of intelligence activities. Indeed, the Committee notes that accountability, and intelligence priorities by extension, have been a core feature of two external reviews of intelligence since the 1980s - one by an Independent Advisory Team and the other by the Office of the Auditor General. Accountability must be constantly renewed to be meaningful. The Committee therefore makes recommendations that it believes will strengthen the accountability, efficiency, and effectiveness of the security and intelligence community.

89. The Committee's review was itself not without challenges. One of the biggest was that NSICOP is legislatively prohibited from seeing "Confidences of the Queen's Privy Council." These confidences are defined in the Canada Evidence Act, and include any information used to present proposals or recommendations to Cabinet; used as analysis or background for consideration by Cabinet in making decisions; contained in records of deliberations for decisions of Cabinet; contained in records used for communication or discussions between ministers; contained in records to brief ministers in relation to matters that are before, or will be before, Cabinet; or contained in draft legislation. Footnote 2 Given that the process for setting intelligence priorities involves memorandums to Cabinet and records of decision, that restriction made it difficult for the Committee to examine and consider ail of the relevant information on this topic. This review and the Committee's findings and recommendations are therefore based on documentation and information, including drafts, created through the intelligence priorities setting process up to the deputy minister level. The Committee believes it was sufficiently informed to make its findings and recommendations.

A short history of Canada's intelligence priorities

90. The process for setting intelligence priorities is described by PCO as "the primary mechanism available to the Prime Minister, Cabinet and senior security and intelligence officials for exercise and control, accountability and oversight of Canada's intelligence production." Footnote 3

91. The process has evolved over time. Cabinet first set national intelligence priorities in the 1970s, but these were narrowly defined and focused on foreign intelligence. In 1987, an Independent Advisory Team led by the Honourable Gordon Osbaldeston examined the newly created CSIS. The report, People and Process in Transition, made several recommendations, including that "the primacy of the role of the political executive in the provision of direction in the national security framework must be re emphasized," and that CSIS should seek Cabinet approval for its priorities on an annual basis. Footnote 4 Since then, CSIS has sought approval for its security intelligence priorities.

92. Throughout the 1990s, the process of setting Government of Canada intelligence priorities expanded beyond a relatively narrow focus to include other areas, such as defence. The priorities became increasingly detailed and categorized along departmental lines. In 1996, the Office of the Auditor General conducted a review of the accountability of the security and intelligence community in Canada. It recommended "enhancing the national priorities process through clearer tasking against priorities, more timely approvals, a more complete ranking system and systematic assessment of intelligence collection against approved priorities." The community responded by stating that the recommendations coincided with its objectives and that "the development of clear priorities to guide intelligence collection and reporting efforts is more important than ever, given that the Canadian intelligence community has more consumers interested in more topics, while, at the same time, it has fewer resources to do the job." Footnote 5

93. The process continued to evolve in response to new priorities and government direction. After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 in the United States, the Government increased the number of priorities and realigned their importance, but made no major changes to the overall process. In 2006, the Government approved a proposal to refocus the process on a smaller number of ranked strategic themes. These broad themes allowed the priorities to better fit within the mandates of all organizations involved in intelligence in Canada.

94. In 2016, the Government decided not to rank the intelligence priorities in the same way that it had for the previous 10 years. PCO informed the Committee that this was due to a number of factors. Following the 2014-2016 priorities-setting cycle, PCO assessed the security and intelligence community's spending, intelligence production, and requests for collection requirements. It found that, in general, spending levels, intelligence production, and requests for intelligence collection did not align with the ranking of the intelligence priorities. In other words, departments and agencies spend more and have more requests for collection on some lower-level priorities than higher-level priorities. The only exception was the *** priority, where the priority level of those issues and the community's level of effort against them were generally consistent. In addition, PCO noted that many departments that receive intelligence for the purposes of their work, but do not collect it, expressed frustration that their needs for intelligence ranked too low to merit sufficient attention by the organizations responsible for intelligence collection. Other organizations believed that the ranked priorities could be perceived as inconsistent with their different mandates. Moreover, PCO noted that ***. PCO noted that by eliminating the ranking of priorities and addressing the issue at the more detailed level of intelligence requirements (further described below), the security and intelligence community could better respond to these challenges. The intelligence priorities for 2017-2019 are listed on page 38.

What is the process for setting intelligence priorities?

95. For the period reviewed by the Committee, Government of Canada intelligence priorities were set by the Cabinet Committee on Intelligence and Emergency Management. Footnote 6 This Cabinet committee's role was to consider reports and priorities, and to coordinate and manage responses to public emergencies and national security incidents. It was chaired by the Prime Minister, reflecting his or her overarching responsibility for intelligence and national security. The Committee included ministers with responsibility for key organizations that work in the areas of security and intelligence, specifically the ministers of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, National Defence, and Global Affairs. The process to set intelligence priorities is depicted on page 38.

Intelligence Priorities for 2017-2019

Intelligence priorities are broad areas of focus set by Cabinet based on where government departments require information to make decisions or fulfill their mandates. The current intelligence priorities are:

- ***

- ***

- ***

- ***

- ***

- ***

- ***

- ***

- ***

- ***

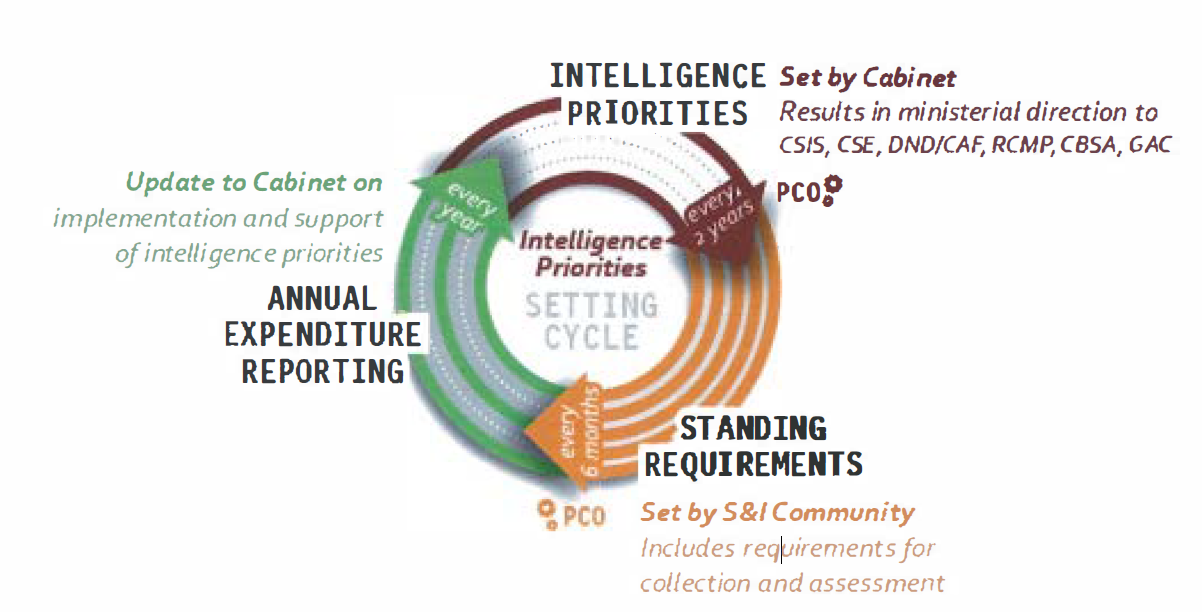

Intelligence Priorities Settings Cycle

- Standing requirements (every 6 months): Set by S&I Community. Includes requirements for collection and assessment

- Annual Expenditure reporting (every year): Update to cabinet on implementation and support of intelligence priorities

- Intelligence priorities (every 2 years): Set by cabinet. Results in ministerial direction to CSIS, CSE, DND/CAF, RCMP, CBSA, GAC

96. The current procedure is for the security and intelligence community to seek Cabinet approval on the intelligence priorities every two years. First, participating ministers are presented with a memorandum to Cabinet drafted by PCO's Security and Intelligence Secretariat. Cabinet decides on the strategic priorities, and a Record of Decision is issued, as per standard Cabinet process. Drawing from this Record of Decision, the Ministers of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, National Defence, and Foreign Affairs, as the ministers responsible for the largest collectors of intelligence, issue direction to their respective organization(s) articulating the priorities and the minister's expectations.

97. The departments and agencies then use those intelligence priorities and the direction they have received from their minister to create the interdepartmental Standing Intelligence Requirements (SIRs), a breakdown of more detailed collection and assessment requirements. The SIRs are reviewed and updated at least every six months. In that process, organizations that collect, assess, and use intelligence articulate their capabilities to respond to the requirements and detail their own intelligence needs. The requirements are updated as necessary based on emerging issues. The ongoing engagement of the security and intelligence community on the SIRs, coordinated by the Security and Intelligence Secretariat, assists in making collection and assessment more responsive to a fluid foreign, security, and defence environment. These processes are coordinated and managed by the Security and Intelligence Secretariat and overseen by the Prime Minister's National Security and Intelligence Advisor (NSIA).

98. Finally, PCO updates the Cabinet committee annually on how the community has supported the intelligence priorities by detailing the implementation and support by each organization. This is done in part through the National Intelligence Expenditure Report, which is managed by Public Safety Canada and coordinated by the Security and Intelligence Secretariat of PCO. This expenditure report includes resource expenditures by intelligence priority and by function (such as collection, production, or support) and is designed to demonstrate to Cabinet the extent to which intelligence production and resource allocation supports the priorities.

99. For many years, the priorities process focused almost exclusively on intelligence collection. In 2013, the Intelligence Assessment Secretariat of PCO and the Integrated Terrorism Assessment Centre were brought into the process. The security and intelligence community noted that this change: led to better representation of intelligence organizations with responsibilities for collection, assessment, or both;

- provided the assessment community with strengthened guidance and direction to facilitate prioritization of assessment production;

- led to closer collaboration between assessment organizations and their security and intelligence partners; and

- brought a wider spectrum of intelligence - collection and assessment - under the intelligence priorities governance and accountability framework.

The result is that government direction on intelligence now includes ail relevant organizations.

Governance

100. The intelligence priorities are intentionally broad. They are designed to capture the government's strategic policy and operational requirements and be relevant to the various mandates of the departments and agencies involved in intelligence. Those organizations include:

- the two largest intelligence organizations, CSIS and CSE;

- departments involved in intelligence, either as collectors or assessors or both, such as the Department of National Defence/Canadian Armed Forces (DND/CAF), Global Affairs Canada, the Integrated Terrorism Assessment Centre, and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP); and

- organizations that are significant clients of intelligence but with a primary role outside of intelligence, such as Transport Canada and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

101. The security and intelligence community is involved in this process at multiple levels. PCO, in the form of the NSIA and the Security and Intelligence Secretariat, leads and coordinates the process. The Secretariat writes the Memorandum to Cabinet in coordination with the security and intelligence community, and leads the interdepartmental process to develop the detailed SIRs. At the deputy minister level, the NSIA co-chairs the Deputy Minister National Security Committee, the primary committee at the deputy minister level for strategic conversations about intelligence and national security. This committee considers the draft memorandum and recommends that it be provided to Cabinet. Those deputy ministers are responsible for ensuring departments are responding to and compliant with ministerial direction. Footnote 7

102. At the Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM) level, the Security and Intelligence Secretariat chairs the ADM Intelligence Committee that approves and attests to the requirements, performance measurement, and resource allocation. At the working level, the Security and Intelligence Secretariat leads several working groups that hold detailed negotiations and discussions on the prioritization of specific requirements. These committees and working groups help to support Cabinet in setting and responding to the intelligence priorities. The Security and Intelligence Secretariat's role in this process is fulfilled with minimal resources. ln a briefing note to the Assistant Secretary for Security and Intelligence, officials noted that there was " *** devoted to supporting the intelligence coordination activities" and that "with current resource levels, we have not been able to maintain consistent levels of coordination with the intelligence community." Footnote 8

103. PCO is ideally placed to provide governance and leadership on intelligence priorities. Under the NSIA, the Security and Intelligence Secretariat directly supports the Cabinet committee responsible for considering the intelligence priorities. Its role is to advise Cabinet on security and intelligence issues from the broadest governmental lens, and is therefore well placed to play a leadership, coordination, and mediation role in the development of the Memorandum to Cabinet and through its supporting processes. This model has been noted by allies with similar governmental structures. ln Australia, the 2017 Independent Intelligence Review recommended that the Australian government centrally coordinate its intelligence as its allies, including Canada, have done. The report stated that more effective coordination would "enhance . . . Ministerial responsibility and the intelligence community's accountability to the Government " and that "enterprise-level management . . . will complement the statutory responsibilities of agencies." Footnote 9 While Canada's system has a structure in place to provide coordination and management, investment and focus have been lacking. For this system to be optimal, strong and sustained central leadership and governance are necessary.

Ministerial Direction

104. Following Cabinet's approval of the intelligence priorities, the ministers responsible for each of the primary organizations involved provide written direction articulating their expectations for how each organization will respond to the priorities. Which organizations receive ministerial direction has changed over time. In the past, direction was generally provided only to the core departments and agencies involved in the collection of intelligence - CSIS, CSE, the RCMP, DND/CAF and Global Affairs Canada. Beginning with the 2017-2019 intelligence priorities, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) also received Ministerial Direction on implementing those priorities. Ministerial direction for enforcement organizations, the RCMP and CBSA, is drafted to preserve their operational independence.

105. Ministerial direction tailors the intelligence priorities to the specific legal mandates and operational responsibilities of the organizations. For example, direction to CSIS would highlight the priorities directly related to the CSIS mandate, such as [*** name of priority ***]; direction to the RCMP would highlight [*** name of priority ***].

106. In the current system, once the Cabinet record of decision is issued, each organization writes its own direction for its minister's approval. This causes some important inconsistencies. In some cases, departments or agencies were not timely in drafting the direction. Footnote 10 Delays in providing ministerial direction may affect the responsiveness of government organizations to new direction and the timing of intelligence collection. Delays may affect the accuracy and scope of performance reporting back to Cabinet, particularly when priorities change. Delays may also put organizations and their management at risk. Footnote 11 Ministerial directions exist in part so that when a department or agency undertakes national security or intelligence activities, the minister can be accountable for those activities. If they are issued late and a problem arises, the minister may not be able to confirm that she or he was aware of what the organization was doing.

107. The Committee discusses these latter two issues in more detail later in this chapter. The Committee also notes that some ministerial direction contained inconsistencies in wording or expectations, which may affect subsequent performance reporting to Cabinet. For example, in 2017-2019, the Ministerial Direction drafted by CSIS excluded two of the priorities, [*** names of priorities ** *], and the [*** names of priorities ***). Footnote 12 Of note, the omission of [*** name of priority ***) created confusion within CSIS over whether its officers could collect intelligence on an issue that was an intelligence priority, had been identified as a very high priority of the community in the SIRs, and was within the mandate of CSIS to collect. Footnote 13 These inconsistencies undermine the effectiveness and efficiency of the community and the Minister's accountability.

108. Led by PCO, the community is taking specific measures to address issues related to consistency and timing of the Ministerial Directions associated with the intelligence priorities. These measures also aim to enhance the role of the NSIA in monitoring performance with respect to this aspect of the process. Footnote 14

Standing Intelligence Requirements

109. The SIRs are a list of specific requests from clients for collection or assessment based on the intelligence priorities. Simply put, the SIRs reflect the intelligence that departments need to do their jobs. Currently, there are over 400 Requirements. The SIRs are ranked into four tiers by importance and the risk or threat that they pose, based on criteria approved by the Government in 2016. Updated every six months and on an ad hoc basis when issues emerge, they are negotiated at the working level and approved by the ADM Intelligence Committee.

110. The SIRs seek to provide an overall picture of what the community is collecting and assessing, where there are gaps, and in what areas the community remains dependent on reporting from allies, such as the Five Eyes. ***. The SIRs can also provide details on how much individual organizations, and the security and intelligence community as a whole, can address (i.e., collect on or assess) any priority or requirement. This type of information is vital for accountability: to provide informed direction, ministers need to have enough information to understand the implications of their decisions.

111. The Committee is concerned that Cabinet may not have access to information that would inform its decision-making. In 2016, PCO introduced a new framework to improve the process for prioritizing the many specific demands of the community within the SIRs. In 2017, the community also considered a new approach that would provide more detailed reporting to Cabinet, including:

- an estimate of the capacity and intention of each organization to either collect on or assess the SIRs;

- which priorities generate the most demand for collection through the SIRs process; and

- the top intelligence targets of the community as a whole.

112. This option would have shown that the community had the capacity and intention to collect on *** percent of SIRs identified at the highest level of importance and on *** percent on the SIRs overall. A PCO document drafted in preparation for the ADM Intelligence Committee noted that the approach was, "an opportunity to use useful data that is generated through the requirements process to support strategic-level discussion on intelligence coordination." Footnote 15 However, a much later draft considered by the community did not contain the detail listed above. Instead, the draft provided a chart showing, in order, the intelligence priorities by "level of intelligence effort," Footnote 16 but without quantified data. The Committee does not know whether the more informative data generated by the interdepartmental working group was ultimately provided to Cabinet, but it does believe that specific data would provide ministers with valuable context. PCO informed the Committee that it is considering options for making better use of the information generated through the SIRs to develop more strategic assessments on intelligence demand and support. Footnote 17

113. The Committee discussed the processes for setting the intelligence priorities and the SIRs with several organizations at hearings. Two themes emerged: the challenge inherent in the level of detail of the SIRs, and the constant pressure to add more to the list. CSE noted to the Committee that the community has many tactical conversations around the SIRs, but that there is room for more strategic discussion around the SIRs and their context within the process to set the intelligence priorities. Footnote 18 The Committee agrees that such an overview would be of benefit to Cabinet. A full picture of government capacity to address the SIRs and the priorities from which they derive, including where compromises have been made, would enable Cabinet and ministers to make informed decisions about trade-offs and risk management. Without those strategic considerations, the demands for intelligence become increasingly unmanageable.

114. The Committee is concerned that the security and intelligence community may be reaching that point. Demands for intelligence that have been identified in the interdepartmental process have resulted in a great many SIRs: currently there are over 400 separate requirements. At hearings, the Committee heard a consistent message from all departments and agencies involved in this process: there are too many SIRs, making the process "cumbersome" and less responsive than most participating organizations would like. For its part, Global Affairs Canada, the largest client organization, informed the Committee that it must be more rigorous in its own internal prioritization to decrease the number of demands it is making for collection and assessment and to enhance focus. Footnote 19 PCO also noted that the community needs to develop tools to manage these challenges strategically. Footnote 20 The Committee is aware that PCO has made other efforts in the last several years to streamline the process. With *** percent of SIRs being covered, and *** percent of the highest priority requirements, the Committee believes there is still room for improvement.

115. The Committee is similarly concerned about the completeness of information being provided to Cabinet in other areas. Consistent with subsection 14(a) of the NSICOP Act, the Committee was not able to review the Memorandums to Cabinet on the intelligence priorities: those memorandums constitute a confidence of the Queen's Privy Council, one of four exceptions to the information that NSICOP is entitled to have. Nonetheless, based on information that was provided about the process of developing that advice, the community appears to provide Cabinet primarily with information and anecdotes that highlight where the community has had operational successes and where it has responded to government direction. Footnote 21

116. The community has been less effective at highlighting gaps in collection and analysis, and the trade-offs and risk management associated with collecting intelligence in some areas and not in others (as described earlier, the opportunity cost inherent in prioritization). ln one example of an opportunity cost, the Security and Intelligence Secretariat informed the NSIA that some organizations "have noted that relatively large expenditures on [*** name of priority ***] have continued to increase while pressures related to [*** name of priorities ***] have also grown," but that that information would not be part of the information update to Cabinet. Footnote 22 The Committee recognizes that compromises around intelligence collection and assessment priorities must be made given the relatively small size of Canada's security and intelligence community. For that reason, the Committee believes it is important to ministerial accountability that those compromises be explained to the Cabinet committee and that the implicated ministers receive the information required to properly assess the decisions before them, including to evaluate the risks inherent in prioritization.

117. Ultimately, the process for setting intelligence priorities is important to the functioning, management, and accountability of the security and intelligence community. It provides a forum for discussion and debate, as well as compromise and coordination. However, the process itself is only as strong as the sum of its parts. The goal, which is robust accountability, requires sound management and a consistent and coordinated framework. Ministerial accountability and the effectiveness and efficiency of the community are best served by ensuring that Cabinet has the most complete information at its disposal. As will be discussed later, the decision to use simplified reporting on results, and the lack of consistent investment in the process to further develop reporting tools, has weakened the process. Those decisions have also contributed to inconsistencies by some organizations in this process. The Committee turns to this issue next.

Operationalization

118. The Committee reviewed how the individual departments and agencies involved in this process operationalize the intelligence priorities and the SIRs, that is, how they take the priorities and develop specific collection plans. Most departments and agencies have created methods for articulating the priorities and requirements into specific direction and guidance for their own activities. The three largest - CSIS, CSE, and DND/CAF - have formalized processes. These processes further refine the SIRs in the context of the mandate, capabilities, and direction of each organization.

119. Each organization uses similar methodologies to develop internal priorities. Each uses weighted methods (assigning a point value to an issue based on its importance to the community, the tiering of the SIRs, the direction of the minister, the relevance to its mandate, and the organization's capacity and ability to collect) to develop internal documents that provide working-level collectors with detailed direction that guides collection and tracks performance. These documents are CSIS's Intelligence Requirements Document, CSE's National SIGINT Priorities List, Footnote 23 and DND/CAF's Strategic Defence Intelligence Requirements.

120. This tailoring of the SIRs is important to ensure that priorities and requirements align with the individual mandates of the specific organizations responsible for intelligence collection and assessment, and to provide sufficiently detailed direction to officials responsible for the organization's intelligence activities.

121. The processes for setting intelligence priorities and establishing the SIRs allow for variance in how much is required of an organization based on its role in the security and intelligence community. The highest expectations for participation and reporting are on the two primary collectors of intelligence: CSE and CSIS. Those two organizations have in the past few years adopted significantly different approaches to meeting those expectations.

The Communications Security Establishment

122. CSE is Canada's signals intelligence agency. It is the only organization with a statutory requirement - that is, required by law - to provide intelligence in accordance with the intelligence priorities. Footnote 24 As a result, CSE is heavily invested in the process to set intelligence priorities. This investment has resulted in a rigorous, consistent, and timely internal process to support the overall intelligence priorities. CSE uses the intelligence priorities and the SIRs to develop internal collection priorities that allow it to respond to government and client priorities and needs. CSE reports the results of its performance and expenditures to its minister through an annual report and to Cabinet through the intelligence priorities process (that is, through the interdepartmental Memorandums to Cabinet and related updates). ln addition, CSE has made strategic decisions regarding its resource allocation based on the priorities and the SIRs, expending approximately *** percent of its resources on the highest priority requirements. Footnote 25

The Canadian Security Intelligence Service

123. CSIS also has an internal process to translate the broader priorities and requirements into collection priorities that are used to drive its operations, reporting, and assessment. Like CSE, this is a longstanding process that also allows CSIS to track its collection and production for reporting purposes. That internal direction is updated every six months following the updating of the SIRs. However, CSIS senior management approved the internal direction (a necessary step) in September 2016 and then not again until April 2018, resulting in an implementation gap that exceeded a year. Footnote 26 CSIS officials informed the Committee that this lapse in implementing the internal requirements had no material impact on CSIS collection activities because there were no fundamental or significant differences between the previous priorities and requirements and the new ones. CSIS stated that it continued to collect intelligence on threats to the security of Canada and maintained that it was always compliant with Ministerial Direction. Footnote 27

124. In the Committee's view, this delay by CSIS affected the entire security and intelligence community. The reliance on outdated or inaccurate internal requirements will make it difficult to fully account for CSIS activities and to provide the most complete information to Cabinet on how the intelligence priorities were supported. Also, CSIS will not be able to provide reliable production measures on the SIRs. This will mean that the security and intelligence community will face challenges in evaluating its overall coverage of the SIRs and the intelligence priorities. The Committee believes that this lapse weakened the accountability that the system was intended to provide.

125. Finally, there is the example this sets for the community. As the Committee noted in its introduction, the intelligence priorities setting process has improved over the years - an acknowledgement made by every department and agency involved. This process, however, is only as strong as the sum of its parts. CSIS and CSE are the most important intelligence collection organizations in the government. As such, the Committee expects that CSIS would take a leadership role in developing and implementing the intelligence priorities and the SIRs and measuring its ability to respond to them.

126. As a result of this review, CSIS noted to the Committee that it has initiated new oversight structures and several improvements to the way it directs and prioritizes collection efforts to better understand client needs. It is also undergoing a review of its intelligence requirements system to assess the manner in which it translates the intelligence priorities into requirements and direction for its collection activities. CSIS is working with PCO to support ongoing improvements to the SIR process. Footnote 28

Assessment organizations

127. The intelligence priorities process has become more inclusive with the formal addition, in 2013, of the Intelligence Assessment Secretariat of PCO and the Integrated Terrorism Assessment Centre. By bringing these assessment organizations closer in line with government priorities and the requirements of the community, client organizations (i.e., those departments and agencies that obtain intelligence and assessments to support their legal mandates) stated that they receive more relevant analysis and more informative products on their areas of operation. Footnote 29 Departments and agencies noted that the assessment of intelligence provides context and perspective on the intelligence available to the community, and stated that the inclusion of the assessment organizations in the intelligence priorities process had been of benefit to the process and the security and intelligence community. This inclusion also provided an opportunity for the Integrated Terrorism Assessment Centre to communicate directly its requirements and preferences with respect to intelligence requirements and priorities independent of others in the community, including CSIS, on whose premises it is co-located.

128. In addition, the Committee was informed that the inclusion of intelligence assessment as part of the intelligence priorities process has started to reach beyond stand-alone assessment organizations. For the first time, CSIS shared its assessment production plan with the working group for the SIRs and the ADM Intelligence Committee. CSIS shared this information in "an effort to be more transparent, enabling better de-confliction and coordination within the [security and intelligence) analytic community." Footnote 30 The Committee sees these trends as positive developments.

Resource expenditures and performance measurement

129. Another aspect of accountability is measuring performance and expenditures against priorities. Over the last decade, successive governments have emphasized the value of measuring the performance of government operations and have implemented new means of tracking organizational performance and accounting for related expenditures. These are important means of ensuring control and accountability. The importance of assessing the effectiveness of government work and aligning resources with priorities was most recently expressed in the Prime Minister's mandate letters to each of his ministers. Unlike other areas of democratic accountability, the security and intelligence community presents unique challenges because of the secrecy of its work. It is therefore important that Cabinet and ministers have measures in place to properly account for performance and expenditures as they relate to the intelligence priorities. This is a significant challenge facing the security and intelligence community in Canada and those among our allies, not least because of the difficulty in measuring success in a security and intelligence context. Footnote 31

130. Efforts to improve accountability in intelligence began with a review of expenditures. In 2011, the Government initiated the National Security Expenditure Review. This review was designed to measure the spending and resources used to support the intelligence priorities. Organizational responses to the expenditure review varied considerably. The Government had requested expenditure information on how the departments and agencies were allocating money and resources to supporting the intelligence priorities. The first iteration, in 2012-2013, was coordinated by the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS). TBS noted that the reporting from each department and agency showed no consistency in terms of what was measured and how, and that there was a lack of clear focus on distinguishing between spending on intelligence versus intelligence-led activities. Essentially, the information from the various organizations of the security and intelligence community could not be reconciled to provide a clear picture of expenditures on the intelligence priorities.

131. Early in the 2014-2016 cycle for setting the intelligence priorities, the community understood that it needed to establish the necessary standards, leadership, and processes needed for more robust horizontal intelligence expenditure and performance reporting. Footnote 32 In other words, the community needed to expand performance measurement beyond individual intelligence programs to include how intelligence is used throughout each organization. In 2015, the NSIA considered options for developing a system of performance measurement within the security and intelligence community in response to Government direction for more robust horizontal reporting. PCO informed the NSIA that,

beyond providing high-level indications of responsiveness to strategic direction, the current reporting framework doesn't adequately [cover] how well or how efficiently [original emphasis] the community works in delivering on the priorities. This latter interpretation of performance is consistent with the Auditor General's 1996 recommendations to integrate performance reporting into the priorities process. The intent was to provide senior officials with additional tools to improve community performance in support of the priorities. Footnote 33

132. PCO presented the NSIA with two options. One option was to create a full performance measurement framework that would explain the similarities and differences between the reporting of the organizations involved, but would also require more policy work and investment to implement and an increased leadership role for PCO. The other option was a simplified version focusing on responsiveness rather than performance that could be implemented within that cycle for setting the intelligence priorities. Footnote 34 The NSIA chose the latter option as it met Government requirements and was achievable within the time constraints of the cycle. This had implications for both expenditure and performance measurement, which the Committee discusses below.

Expenditures: What is the security and intelligence community spending?

133. The security and intelligence community provided the Committee information on financial expenditures and human resources. According to this information, the annual expenditure of the Government of Canada in support of the intelligence priorities is approximately * * *, which supports approximately ***. The organizations captured by this data are CBSA, CSIS, CSE, DND/CAF, Global Affairs Canada, the Integrated Terrorism Assessment Centre, PCO, Public Safety Canada, and the RCMP. These organizations' expenditures to support the intelligence priorities account for just over *** percent of their total expenditures (approximately *** of $31 billion) because some of them have additional mandates and functions that are unrelated to intelligence. Footnote 35

134. For expenditures, the updated system initiated in 2014 was developed by PCO, TBS, and Public Safety Canada, and implemented in 2016. The expenditure methodology was revised to demonstrate responsiveness, ensure greater consistency in financial reporting across departments, and better account for how much was being spent to support the intelligence priorities specifically. The changes were also intended to aid accountability and make reporting more consistent with other departmental financial reporting requirements. The review was renamed the National Intelligence Expenditure Review to reflect its emphasis on measuring only those activities and resources that support the intelligence priorities.

135. Notwithstanding these changes, the implementation of the new methodology was inconsistent across departments and agencies. For some departments, the new methodology led to positive change. DND/CAF developed a full methodology for calculating expenditures in support of the intelligence priorities, including methods for capturing relatively granular expenditure details (e.g., the number of aircraft-hours devoted to an intelligence function). For other organizations, the methodology for calculating the support for the intelligence priorities did not result in a corresponding breakdown of expenditures. For example, CSIS claimed 100 percent of its 2016-2017 budget as supporting the intelligence priorities based on its Departmental Results Framework. Footnote 36 Other process challenges included organizational delays in providing relevant information and confusion over differences in methodologies, issues that have been addressed by the community. Footnote 37

136. These inconsistencies create challenges in evaluating the size and scope of the security and intelligence community. For example, when organizations over-report their expenditures on support to the intelligence priorities, the community cannot accurately assess, nor portray to Cabinet, the proportion of overall expenditures that are being spent on the government's intelligence priorities or the relative proportions spent on individual functions, such as assessment or collection. However, PCO notes that the validity of the numbers continues to improve and the community now has six years of annual financial data. Footnote 38

Performance measurement: How well is the community doing?

137. Performance measurement continues to experience significant challenges. To respond to the 2014 decision to provide more comprehensive information, PCO developed a Performance Measurement Framework in 2015. As noted above, this was intended to measure how well and how efficiently the community was delivering on the intelligence priorities. Specifically, the draft framework identified four areas of importance:

- to provide information that could inform potential resource trade-offs within the community;

- to provide context for discussions on costs associated with different intelligence priorities and to understand how coordination and partnerships contribute to addressing the priorities rather than just examining the efforts of individual organizations;

- to provide clear measures of the capacity of each organization to address each priority and its ability to realign or shift its efforts when required to enable senior officials and Cabinet to consider significant gaps; and

- to provide insight into the community's capacity to disseminate intelligence in a timely and effective way to clients and the clients' capacity to manage and make the best use of the intelligence they receive. Footnote 39

138. This proposed framework was part of the more comprehensive option for performance and expenditure measurement considered by the NSIA in 2015. The NSIA opted to proceed with more simplified reporting that focused on responsiveness to the intelligence priorities instead of performance, which was more easily implemented. As a result, this framework for establishing community standards in performance measurement was never used. Instead, the community concentrated on measuring expenditures and production.

139. Measuring production (that is, the number of intelligence reports produced) without measuring performance to provide context presents challenges. Many organizations are faced with the challenge of counting production when reports cannot be easily categorized. While the practice of double (or multiple) counting is consistent with PCO direction, it results in considerable overlap in calculating production without any context to explain the discrepancies. While double counting may help the community and Cabinet identify where there is overlap in collection and assessment, it may also obscure how responsive the security and intelligence community is to specific priorities.

140. CSE sought to address this issue in 2015. That organization noted that, on average, 16 different intelligence requirements based on SIRs were identified for each report Footnote 40 - a flawed measurement of how well the organization was responding to the requirements and priorities. [*** The following text was revised to remove the names of specific priorities: For example, a long report on one priority may contain a single line referring to an organization but with no further context. That report would be automatically recorded as responding to both priorities, when in reality the intent of the report was the first priority. ***]. In response, CSE implemented a tagging system whereby analysts identify the intent behind the reports by referencing specific SIRs. This allows CSE to provide metrics that reflect the intent of its reports, rather than relying on automated keyword associations. CSE also tracks its reports based on client feedback, including whether the report was read by at least one client, and whether it satisfied needs, was exceptional, or was actionable. Footnote 41 These methodologies combined to provide both quantitative and qualitative performance measurement of the value of the intelligence production.

141. This issue of measuring production without measuring performance to provide context affects other organizations as well. For example, the Intelligence Assessment Secretariat of PCO reported that it produced *** reports in 2017-2018. This is partially due to the Secretariat counting as a separate report each summary item within its *** (a document produced for senior government and political officials ***), and counting other single reports multiple times if they respond to more than one priority. Footnote 42

142. The Committee was informed that the security and intelligence community continues to consider how to address these challenges and improve its capacity for measuring performance. The Committee understands that measuring performance in intelligence is difficult, a challenge faced by ***. PCO, which would coordinate such work, does not currently have the resources available to develop or implement substantial improvements. Nonetheless, performance measurement is important for accountability. Performance indicators give context to the expenditure information that the community provides to Cabinet for decision-making, which in turn supports the management of the community through identifying and understanding compromises, priorities, and areas for possible efficiencies.

Conclusion

143. The Committee concludes that the process for setting the intelligence priorities is fundamental to ensuring accountability over an area of operations that is high in risk because of its sensitivity and potential impact on the rights of Canadians and because, of necessity, it is sheltered from public scrutiny. It is an essential mechanism to coordinate and maximize the activities and resources of the departments and agencies in the security and intelligence community. Indeed, the government establishes the priorities so that the departments and agencies can better determine where to expend their limited resources to collect, assess, and disseminate intelligence. Prioritization, compromise, and burden sharing are integral to the success of Canada's security and intelligence community, given its size and scope.

144. The Committee recognizes that improvements have been made in the process over the years. Given its importance, the process should be as robust as possible. This review has revealed a number of weaknesses:

- ministerial direction is not always promptly issued, consistent with the priorities, or fully implemented by organizations;

- the SIRs need to be reconciled with the capacity of the Canadian security and intelligence community;

- the community needs to ensure that Cabinet is receiving all relevant information to enable it to make decisions; and

- systems to track performance measurement are underdeveloped and systems to track financial expenditures inconsistent.

145. These issues are important and they should be addressed. Without a full understanding of limitations and weaknesses of intelligence, without full participation and engagement by participants, and without strong and consistent coordination and management, accountability is undermined. The Committee believes that its recommendations will contribute to a more robust and, ultimately, accountable process.

Findings

146. The Committee makes the following findings:

F1.

The process for setting intelligence priorities has a solid foundation and overall participation by the community has made it more rigorous, inclusive, and systematically applied. Coordinating the timing and consistency of Ministerial Directions to organizations involved in the intelligence priorities process would add rigour to the process, strengthen the development of the Standing Intelligence Requirements, and increase the accountability of ministers.

F2.

Coordinating the timing and consistency of Ministerial Directions to organizations involved in the intelligence priorities process would add rigour to the process, strengthen the development of the Standing Intelligence Requirements, and increase the accountability of ministers.

F3.

The great number of Standing Intelligence Requirements, particularly at the highest priority level, makes it difficult for the community to ensure that Cabinet has the information it needs on the significance of identified gaps in collection and assessment.

F4.

In general, the internal processes that NSICOP examined were effective and enforced.

F5.

The delay by CSIS in updating its internal Intelligence Requirements Document to incorporate the new intelligence priorities and SIRs in a timely manner undermined the accountability of both the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness and Cabinet, and weakened the accountability of the overall system to support those priorities.

F6.

The National Intelligence Expenditure Review methodology is not applied consistently by organizations to provide Cabinet with complete and comparable information on how organizational resources are used across government to respond to the intelligence priorities.

F7.

Performance measurement for the security and intelligence community is not robust enough to give Cabinet the context it needs to understand the efficiency and effectiveness of the security and intelligence community.

Recommendations

147. The Committee makes the following recommendations:

R1.

The National Security and Intelligence Advisor, supported by the Privy Council Office, invest in and take a stronger managerial and leadership role in the process for setting intelligence priorities to ensure organizational responses to the intelligence priorities are timely and consistently implemented.

R2.

The security and intelligence community develop a strategic overview of the Standing Intelligence Requirements to ensure Cabinet is receiving the best information it needs to make decisions.

R3.

Under the leadership of the National Security and Intelligence Advisor and supported by the Privy Council Office, the security and intelligence community develop tools to address the coordination and prioritization challenges it faces in relation to the Standing Intelligence Requirements.

R4.

The security and intelligence community, in consultation with the Treasury Board Secretariat, develop a consistent performance measurement framework that examines how effectively and efficiently the community is responding to the intelligence priorities, including a robust and consistent resource expenditure review.